Why is it so hard for some people to let Willa Cather be queer, both to herself and the world? In Chasing Bright Medusas: A Life of Willa Cather (2023), Benjamin Taylor treats Cather’s sexuality as an enigma. On Cather’s sexuality during her years as a student at the University of Nebraska, for example, he writes, “Willa saw herself as exceptional rather than homosexual. But that she was homosexual is obvious, astounded though she would have been to know it.” He gives some attention to a woman whom he calls Cather’s “great love” (Isabelle McClung Hambourg), as he does to Edith Lewis, the woman with whom Cather lived in New York City for nearly 40 years. However, he also gives great weight to what he describes as Cather’s “antipathy to sexual love” in her fiction (and, by implication, her life). “Sex….is the worm in the apple” he writes, unhappy marriages predominate, and “sexual need is the flaw in human nature. She was against it; her great protagonists rise above it.”

In Maureen Corrigan’s review of Taylor’s book, featured on the front page of Washington Post Books (12 November 2023), she celebrates the recognition Cather is receiving keyed to the 150th anniversary of her birth, and drawing on Taylor, leans into the supposed inscrutability of Cather’s sexuality. Calling Taylor “an especially nuanced commentator on the vexed ‘Was she or wasn’t she?’ question of Cather’s sexuality,” Corrigan suggests that Cather wished to be “done with” sex and carnal desire so that she could devote “sustained effort” into making herself a great artist.

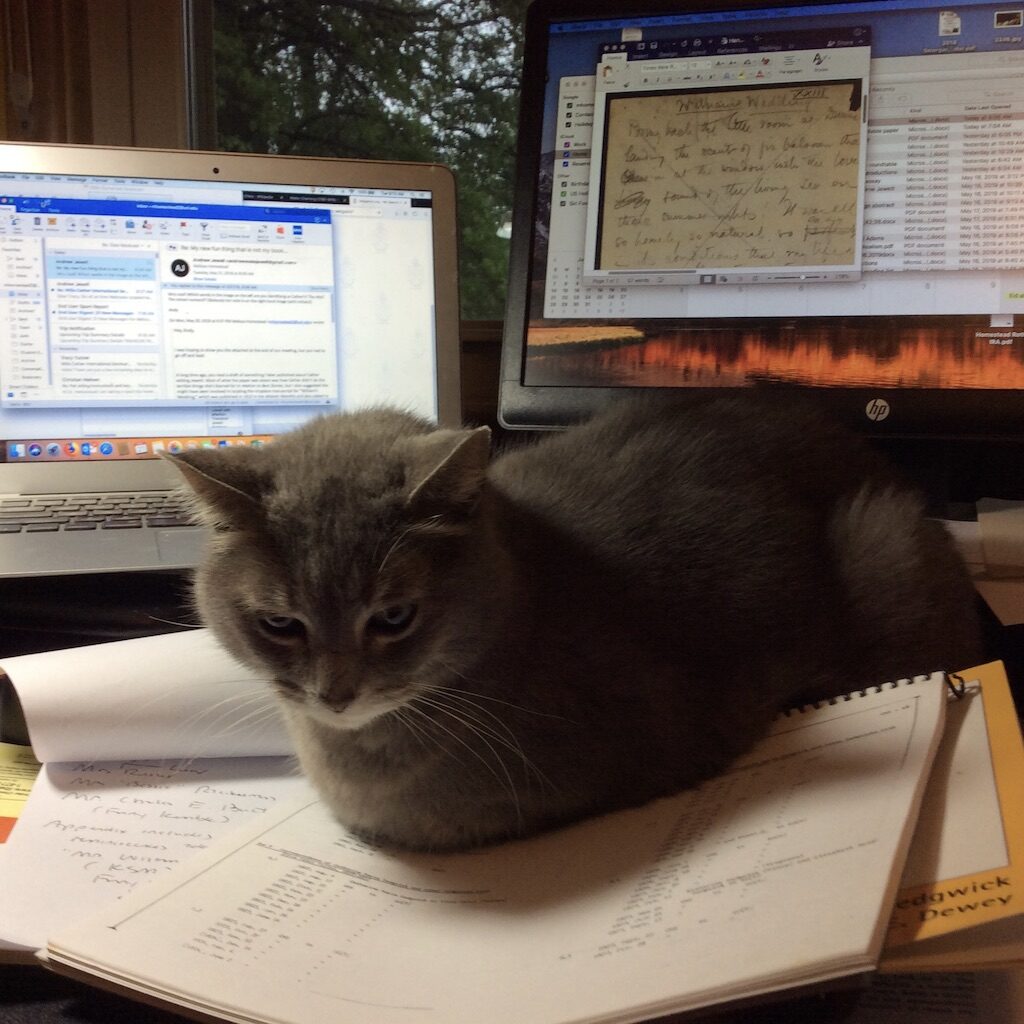

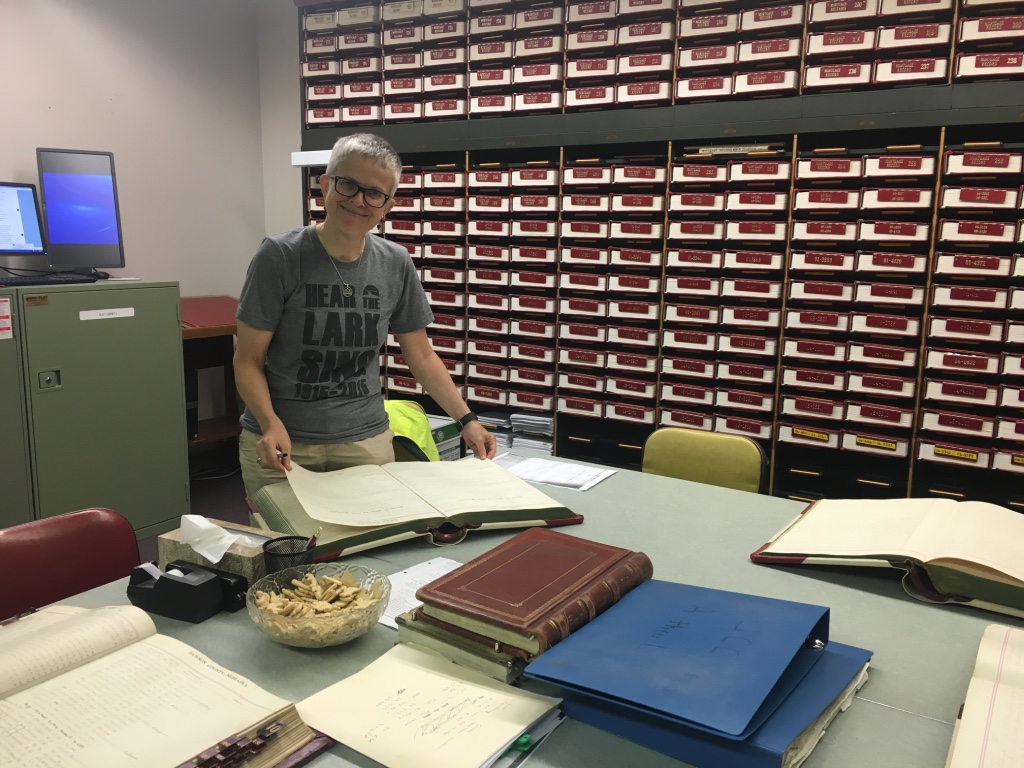

If Cather had lived openly with a man for as long as she lived with Edith Lewis, would anyone find Cather’s sexual identity and the nature of the relationship a mystery? Notably, Taylor’s account of Lewis is scant and error-filled. He fails to mention Lewis’s role as Cather’s editor, shaping her “late style” he so admires, and he closes his book with the debunked idea that Lewis is buried at Cather’s feet (she is at Cather’s side, as she was in life).

By claiming Cather’s queerness, I am not trying to turn her into a role model, nor am I suggesting that the “common readers” who are “ready to explore Cather’s life and work” and to whom Corrigan recommends Taylor’s book must read Cather’s fiction through her sexuality–it is Taylor who does that. An accurate account of Cather’s life is my concern. The letter to university classmate Louise Pound that grounds Taylor’s claim that Cather thought of herself as “exceptional rather than homosexual” is, as he accurately characterizes it, “a profession of love.” However, he also claims that the letter is about “love at its most exalted, above the reach of mere carnality” and that “No other letter like it survives.”

Even though Corrigan characterizes Taylor’s account of this letter as typical of his “rigorous effort to fathom how Cather understood herself,” neither of Taylor’s claims about the letter is accurate. The letter begins with a paragraph of Cather’s comments on how “very handsome” she found Pound in her French couture gown the evening before, and in a later paragraph she says three times how “queer” she felt. “I wanted very much to ask you to go through the customary goodbye formality,” she explains (meaning that when she left a party they both attended, she wanted to hug and kiss Pound), “but I thought it might disgust you a little so I did’nt.” In the following yearning run-on sentence, Cather again expresses her desire for physical contact with Pound the evening before and imagines a time in the future when both of them might laugh at her intense feelings. How is this a letter about “love above the reach of mere carnality”?

Unfortunately, Corrigan is not the only reviewer to point to Taylor’s inaccurate and, frankly, baffling claims about this letter as typical of his astute take on Cather’s sexuality. Certainly, this letter and others Cather wrote in the 1890s suggest that Pound did not reciprocate her feelings, but Cather had most of her life ahead of her, including the years that she lived with Edith Lewis. Is Cather’s beautiful, subtly erotic 1936 letter addressed to “My darling Edith” from which I took the title of my book The Only Wonderful Things: The Creative Partnership of Willa Cather and Edith Lewis not a profession of love? A love letter written to a woman with whom she had been living for twenty-eight years at the time she wrote it? In his biography of Marcel Proust, Taylor has no difficulty recognizing Proust’s homosexuality, but lesbians, it seems, are harder to see.

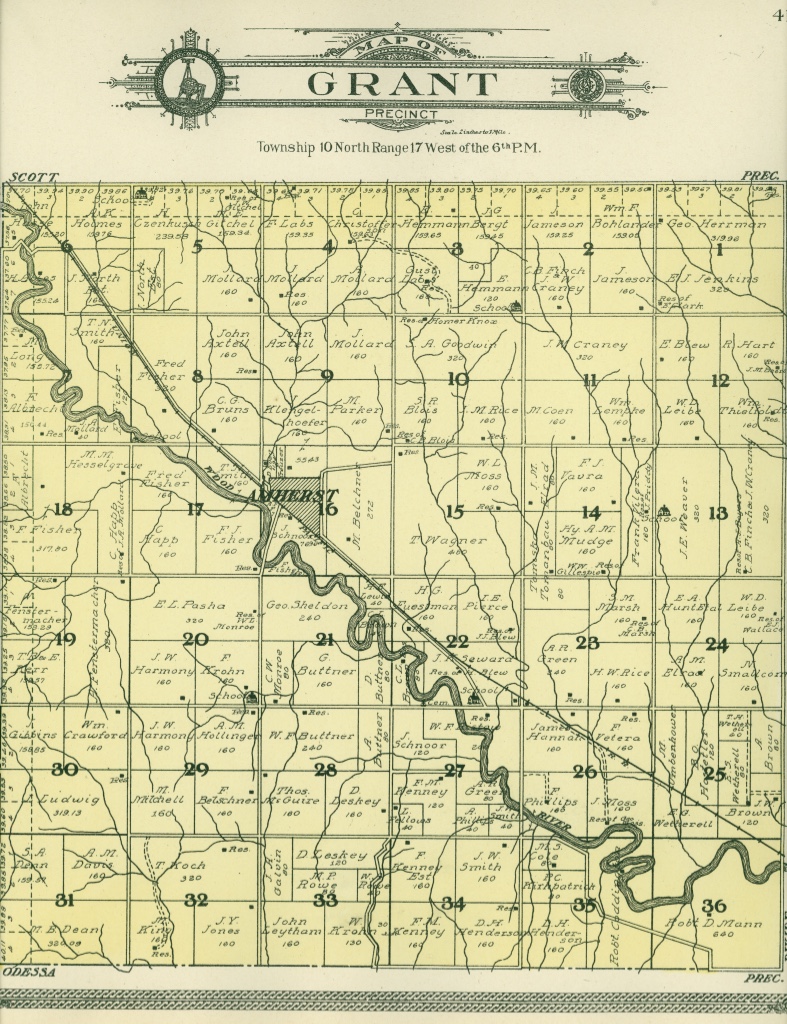

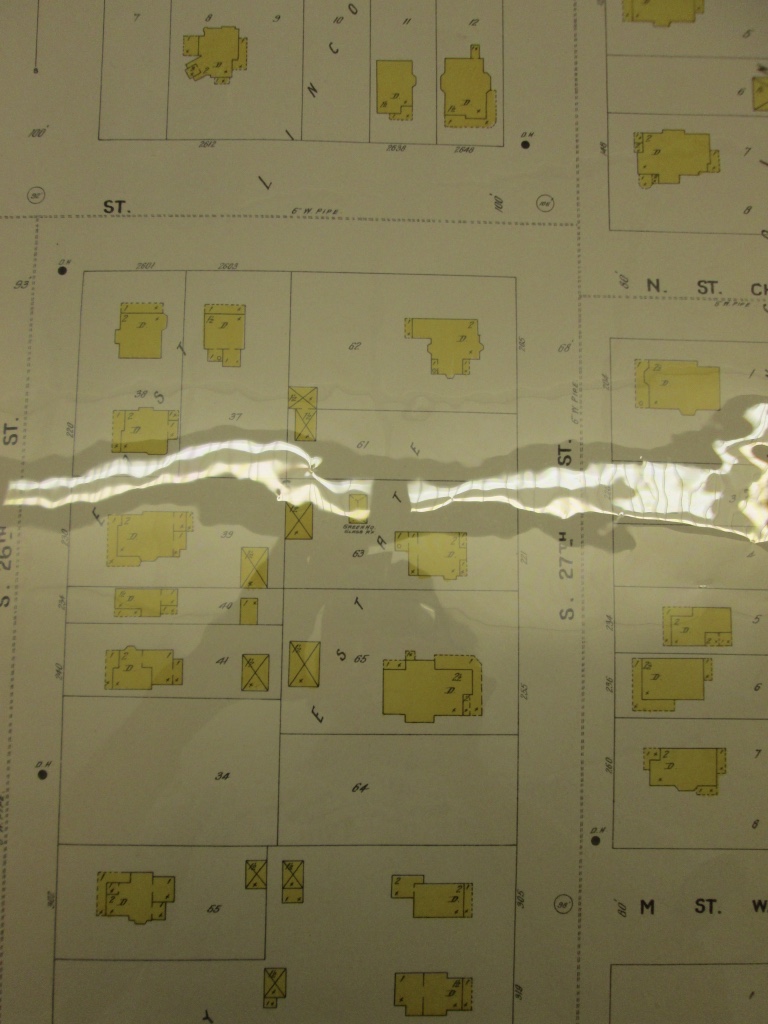

Perhaps Cather’s anti-modernism and childhood and adolescence in Nebraska, both central to Taylor’s reading of her life and fiction, make her queerness seem inscrutable. If, as common wisdom holds, queer folks flee small towns to major coastal cities, and lesbianism is a modern invention, then Cather (despite her own career trajectory away from Nebraska) couldn’t be queer. Such cultural assumptions fail to account for the diversity of Midwestern and rural experience in the past or today. As an adolescent in the 1880s and 1890s in Red Cloud and Lincoln, Cather presented to the world as William Cather, hair cropped short and dressed in boyish or mannish clothing. In 1893, William began to fade as the cropped hair grew long and the feminine-presenting Willa Cather emerged, living as a woman who formed romantic attachments with other women.

In Nebraska today, many of us are here and queer—in Lincoln (where I live and teach) and Omaha, but also in the rest of this largely rural and agricultural state. In June 2023 at the Willa Cather Spring Conference in Red Cloud (population 1,000, half its size during Cather’s years there), the young person ringing up my lunch order at Subway correctly read me and a fellow attendee as out-of-town queer folks and excitedly told us about the pride festival that weekend in Hastings (population 25,000, forty miles to the north). I, in turn, told them that I’d be singing with Queer Choir LNK at Lincoln’s Star City Pride Festival. Omaha, Sioux City, Grand Island, Norfolk, North Platte, and even tiny Aurora (population 4,500, hometown of my queer fiction writer colleague Timothy Schaffert) also have pride festivals.

One hundred and fifty years after Cather’s birth, it’s time to stop the endless recycling of the idea that Cather’s sexuality is a mystery and caviling about evidence. She was here (whether Nebraska, Pittsburgh, New York City, or the many places she traveled), she was queer, get used to it.